Suez Fallout and Some Key Shipping Terms You Should Know

Although the memeing of the Ever Given has subsided and any day now we should get an incident report detailing what caused the six-day blockage, shippers and ports around the world are coming to grips with bunches of arriving vessels, equipment feast, and famine. This is just another incident in a fourteen-month string of incidents that will continue to maintain record-high prices for the foreseeable future.

We talked about the near-term practical implications for what happened with the Ever Given and what it meant both for shippers with cargo on board the vessel and for the wider shipping market.

Since a calamity can also be a time of great opportunity, we at TOC decided this would be the optimal time to educate our customers on three ocean shipping terms which we use, that you probably hear frequently and need to know in greater detail. It will be useful for explaining to your managers, owners, and customers why cargo is delayed and equipment in short supply for at least the next several months.

General Average

Whether you’re a shipper with cargo on board the Ever Given or had cargo on a vessel that jettisoned or lost containers at sea in an accident or foul weather, one thing is certain: it will never be the vessel owner’s fault, and they won’t want to pay under any circumstances.

The Egyptian government has impounded the Ever Given and wants $900 million to let it go. They’re calculating lost revenue from the Canal’s closure in their figures. The operation to get the vessel free cost only $2 million.

“If you’d not given it to us, we wouldn’t have had the problem in the first place,” is an extremely casual and technically not incorrect reading of admiralty laws or the terms and conditions on the back of an ocean carrier’s bill of lading.

Once a vessel owner declares general average, every shipper on the boat contributes to making the vessel owner and cargo owners whole. The Ever Given’s owners have declared General Average.

To give you an idea of the cost to shippers on board the vessel in a General Average claim, take these two paragraphs from the story we linked above:

General Average was declared following the 2018 fire on board the Maersk Honam. After declaring GA, the adjustor fixed the salvage security at 42.5% of cargo value and 11.5% as a GA deposit – this meant a shipper with a cargo worth $100,000 needed to pay a combined deposit of $54,000 to get its cargo released.

This leaves shippers with uninsured cargo highly vulnerable to losing it, as the owner can hold the goods under lien until the deposit is paid. Shippers with insured goods will have those deposits covered by their insurers.

Have we asked you lately – is your cargo insured or would you like a quote?

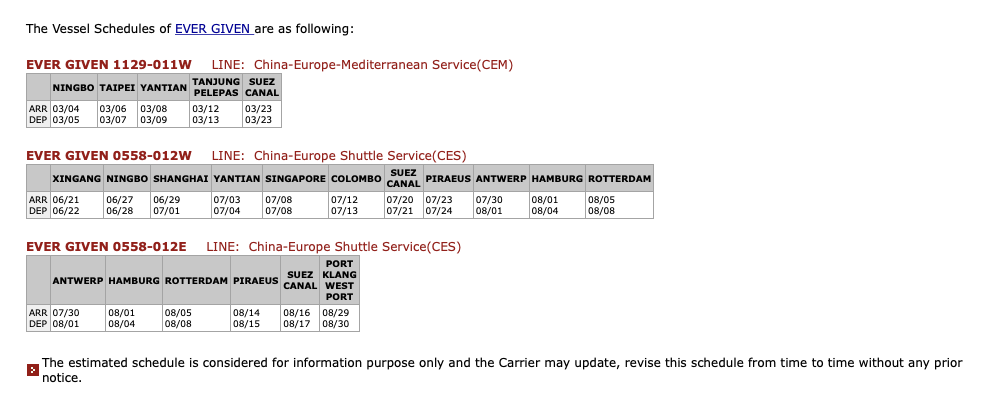

The Ever Given was just one of a number of ships operating Evergreen’s China-Europe-Mediterranean Service, or string.

Ocean carriers operate most services on a fixed day-of-the-week schedule for port calls around the world. Because these services may be a “pendulum” service where the ships go out and back or a “round-the-world” service when they keep traveling and making calls, circumnavigating the globe from east to west or vice versa, it may be months before the same vessel that called in one port is back again.

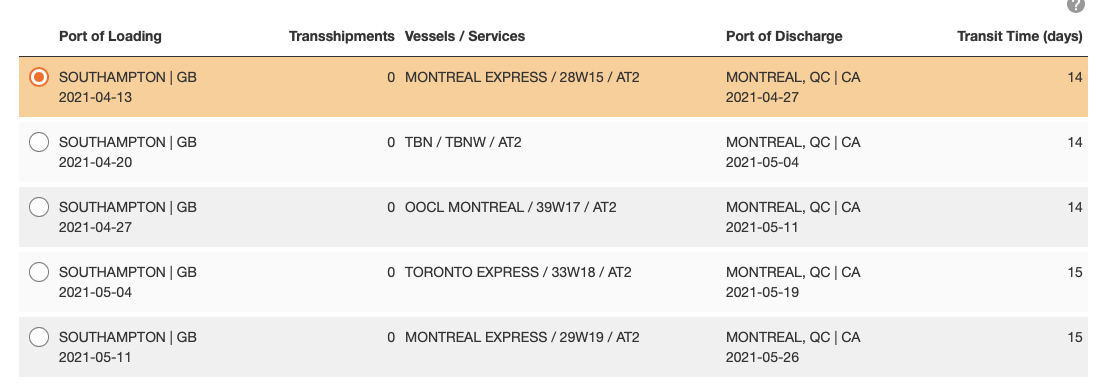

To maintain the schedule integrity of these strings it takes multiple vessels. Take a look at the schedule from Hapag Lloyd’s AT2 service, calling Southampton, Antwerp, and Hamburg in Europe and crossing the Atlantic to call Montreal.

The schedule means that every Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday, a ship on this AT2 service is supposed to be in each of those ports, arriving then in Montreal 11 days after departing Southampton.

The schedule means that every Tuesday, Wednesday, and Friday, a ship on this AT2 service is supposed to be in each of those ports, arriving then in Montreal 11 days after departing Southampton.

So, for Hapag Lloyd to operate the AT2 string, they require four vessels: the Montreal Express, a vessel to be named, the OOCL Montreal, and the Toronto Express before the Montreal Express returns to Southampton four weeks to the day after last calling.

So, for Hapag Lloyd to operate the AT2 string, they require four vessels: the Montreal Express, a vessel to be named, the OOCL Montreal, and the Toronto Express before the Montreal Express returns to Southampton four weeks to the day after last calling.

The AT2 example is great when we’re looking at shipments where the container is loaded on board a vessel at origin and is not discharged until the final port of discharge. But what happens when that container must connect with another vessel in another port to get to the final destination?

Enter transshipment.

Transshipment

Not unlike airlines that run very tight operations a hub airport that leaves you running for your plane with minutes or seconds to spare if something happens to your inbound flight or waiting with hours to spare for your delayed or canceled outbound flight, it’s easy to see how when a vessel nearly as long as the Empire State Building is tall is held up that it can really gum up the works.

This is no different in ocean shipping, where transshipment ports like Freeport, Hong Kong, or Singapore take vessels from feeder ships (smaller and carrying fewer containers from a non-mainline port) and meet up with the larger ships moving between continents.

The delays imposed by the Suez blockage, as well as the blanked sailings in the early stages of the pandemic caused cargo to miss connections or overflow terminals getting in to and out of transshipment ports.

The implication of missed transshipments is the same as missed flights as a passenger. If you miss that one flight to that one destination that day – or in the case of some ocean vessels that week – the implications can be disastrous.

That’s a lot of stuff that can go haywire.

The number of things required to actually keep cargo in motion are not unlike any successful theatre production or scoring drive requiring rehearsals and rote memorization of choreography by the players or actors to succeed.

To the audience, it is an artfully executed performance or tallying of points.

For the participants, it is an intricate exercise in trust, planning, interdependence, and repetition.

Given the inability of the actors and figures to execute on their own, TOC is doing our best to alternately plan puppeteers or Force-choking Jedi Masters in order to drive as many successful outcomes as we can manage.

All we ask of our customers is a constant flow of bi-directional communication that ensures we are taking the right steps that you’re asking us to ensure the performers take on your behalf.

It’s not easy. It never was easy – it’s just inherently and more necessarily complex now than it was before. But working with TOC is a good first step to getting out the other side of this…together.

WE’RE HERE TO HELP

Our capable and experienced team is standing by to assist organizations and supply chains across the globe. Click the button to get in touch with our team.